When Virginia Woolf left her house on the last day of her life on March 28 in 1941, she left behind a note to Vanessa Bell, her sister, and a note to Leonard Woolf, her husband.

The notes hinted that Virginia was going to kill herself but didn’t say how or where. Little did she realize that the river she planned to drown herself in would sweep away her body and prevent her friends and family from discovering what happened to her for three whole weeks.

After the discovery of her hat and cane on the bank of the nearby river Ouse, her family assumed she had drowned herself but had no evidence to confirm it.

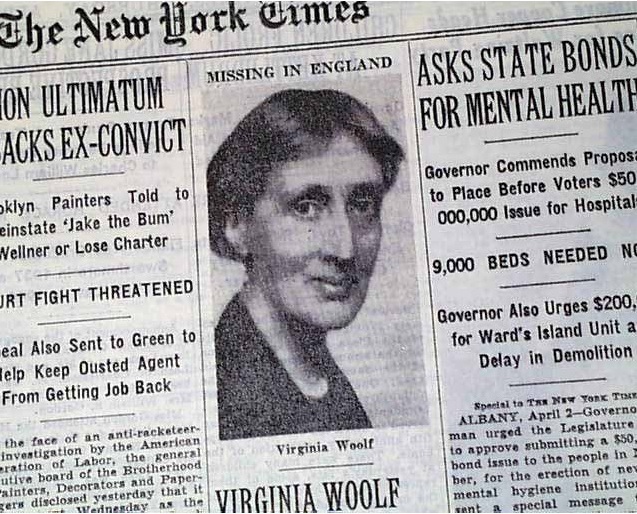

A couple of news articles published during that time frame document the weeks her loved ones, and the world, spent waiting to find out what happened.

In one article, published in the New York Times on April 3, Leonard Woolf is quoted as saying:

“Mrs. Woolf is presumed to be dead. She went for a walk last Friday, leaving a letter behind, and it is thought she has been drowned. Her body, however, has not been recovered.”

The article confirmed Virginia was missing but states the police were not investigating her disappearance:

“The circumstances surrounding the novelist’s disappearance were not revealed. The authorities at Lewes said they had no report of Mrs. Woolf’s supposed death. It was reported her hat and cane had been found on the bank of the Ouse River. Mrs. Woolf had been ill for some time.”

Although there was little doubt that Virginia had killed herself, there was no body, no evidence, no funeral and no closure for her friends, family or her fans. In a letter written by Virginia’s brother-in-law Clive Bell, dated April 3, Bell reveals to his friend, Frances Partridge, that the family had hoped to find her alive but that hope had waned as the days went on:

“For some days, of course, we hoped against hope that she had wandered crazily away and might be discovered in a barn or a village shop. But by now all hope is abandoned; only, as the body has not been found, she cannot be considered dead legally.”

Yet, according to a biography on Virginia Woolf by Nigel Nicholson, some of her friends, such as Nicholson’s mother Vita Sackville-West, thought it best if her body was never found and hoped it was instead carried out to sea so that her loved ones would not have to face it.

Three weeks later, some children made the gruesome discovery when Virginia’s body washed up near the bridge at Southease. On April 19, the Associated Press announced to the public “Mrs. Woolf’s Body Found,” and confirmed she had drowned herself. The article hinted that the ongoing war with Germany may have played a part in her suicide:

“Dr. E. F. Hoare, Coroner at New Haven, Sussex, gave a verdict of suicide today in the drowning of Virginia Woolf, novelist who had been bombed from her home twice. Her body was recovered last night from the River Ouse near her week-end house at Lewes…. Her husband testified that Mrs. Woolf had been depressed for a considerable length of time. When their Bloomsbury home was wrecked by a bomb some time ago, Mr. and Mrs. Woolf moved to another near by. It, too, was made uninhabitable by a bomb, and the Woolfs then moved to their weekend home in Sussex.”

The coroner read a portion of her suicide note to the reporters, but misquoted it. The reporters printed the misquote in the article. The note did not mention the war but Virginia did state she was not well and felt she couldn’t go through another breakdown.

Virginia was later cremated and her remains were buried under one of the two intertwined Elm trees in her backyard, which she had nicknamed “Virginia and Leonard.” Leonard marked the spot with a stone tablet engraved with the last lines from her novel The Waves:

“Against you I fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death!

The waves broke on the shore.”

Virginia’s suicide note to Leonard read:

“Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier ’til this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that — everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer. I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been. V.”

Sources:

Nicolson, Nigel. Virginia Woolf. Penguin Group, 2000.

Flood, Alison. “New Bloomsbury Archive Casts Revealing Light on Virginia Woolf’s Death.” The Guardian, 19 Mar. 2010, www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/mar/19/bloomsbury-archive-virginia-woolf-death

“Virginia Woolf Believed Dead.” New York Times, 3 April. 1941, www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0125.html