Despite her deep English roots, Virginia Woolf was a fan of American writers and felt they were superior to British writers.

According to an article in the Dublin Review, Virginia wrote a number of essays praising American writers as modern, experimental and inventive.

Virginia felt British literature in the 20th century was tired and worn-out and believed that Americans, with their Americanized English and adventurous spirit, were reinventing the art of writing.

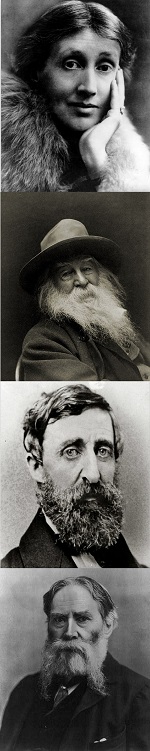

Virginia’s favorite American writer was Walt Whitman. In her 1917 essay titled “Melodious Meditations,” published in the Times Literary Supplement, Virginia heavily praised Whitman, declaring that no British writer could ever compare to him:

“…if anyone is sceptical as to the future of American art let him read Walt Whitman’s preface to the first edition of Leaves of Grass. As a piece of writing it rivals anything we [the English] have done for a hundred years, and as a statement of the American spirit no finer banner was ever unfurled for the young of a country to march under.”

In another essay titled “American Fiction,” published in the Saturday Review of Literature in 1925, Virginia again declared Whitman superior to British writers:

“The English tourist in American literature wants above all things something different from what he has at home. For this reason the one American writer whom the English whole-heartedly admire is Walt Whitman. There, you will hear them say, is the real American undisguised. In the whole of English literature there is no figure which resembles his – among all our poetry none in the least comparable to Leaves of Grass….”

Whitman had a big influence on the Bloomsbury group and specifically on Virginia Woolf’s books. E.M. Forster borrowed the title of one of Whitman’s poems, Passage to India, for the title of his famous book and Virginia quoted lines from Leaves of Grass in her first novel A Voyage Out.

Virginia and her friends were fans of other American writers as well, such as Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell and Henry David Thoreau, whom Virginia wrote an essay about for the Times Literary Supplement in 1917.

Virginia may have inherited her love of American writers from her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, who traveled to America during the Civil War in 1863 and met many writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Eliot Norton, Oliver Wendell Holmes and James Russell Lowell, with whom he became close friends.

Stephen later made Lowell a godfather to young Virginia [Stephen] Woolf when she was born in 1882. Lowell visited the Stephen family often and showered the young Stephen children with presents, especially Virginia, who was his favorite.

Although Virginia wrote many essays applauding American writers, she found herself in some controversy in 1929 after she wrote an essay for the New Republic in which she made a reference to American writer Henry James that touched a few nerves in the United States:

“Thus a foreigner with what is called a perfect command of English and musical English – he will, indeed, like Henry James, often write a more elaborate English than the native – but never such unconscious English that we feel the past of the word in it, its associations, its attachments.”

The magazine received a number of complaints about Virginia’s essay, including one from Harriet T. Cooke which accused her of being condescending:

“Just as a matter of curiosity, I am interested to know what she [Woolf] considers the native language of Henry James – Choctaw, perchance! – since he came from the wilds of Boston. I am quite familiar with that ‘certain condescension’ which the English display towards us benighted Americans, but it is a surprise to learn that we are looked on as newcomers to the English language.”

Virginia responded to Cooke with a long letter in which she defended herself by explaining that she did not intend what she wrote to be an insult and reiterated how much she loved American English:

“…But may I explain that the responsibility for my error rests with Walt Whitman himself, with Mr Ring Lardner, Mr Sherwood Anderson, and Mr Sinclair Lewis? I had been reading these writers and thinking how magnificent a language American is, how materially it differs from English, and how much I envy it the power to create new words and new phrases of the utmost vividness. I had even gone so far as to shape a theory that the American genius is an original genius and that it has borne and is bearing fruit unlike any that grows over here….Why, I wonder, when I say that Henry James did not write English like a native, is it assumed that I intend an insult? Why does your correspondent at once infer that I accuse the Bostonians of talking Choctaw? Why does he allude to ‘condescension’ or refer to ‘us poor benighted Americans’ and suppose that I look upon them as ‘newcomers to the English language’ when I have said nothing of the sort?… ”

Virginia’s only problem with American writers was when they weren’t experimental enough, an accusation she leveled at Edith Wharton and later at Ernest Hemingway in an essay in the New York Herald Tribune books section in 1927:

“At any rate, Mr. Hemingway is not modern in the sense given; and it would appear from his first novel [The Sun Also Rises] that this rumour of modernity must have sprung from his subject matter and from his treatment of it rather than any fundamental novelty in his conception of the art of fiction. It is a bare, abrupt, outspoken book…He is modern in manner but not in vision…Thus Mr. Lawrence, Mr. Douglas and Mr. Joyce partly spoil their books for women readers by their display of self-conscious virility; and Mr. Hemingway, but much less violently, follows suit.”

The essay reportedly angered Hemingway so much that he punched a lamp in a bookshop when he read it and later wrote a letter to his friend Max Perkins, in November of that year, stating:

“The Virginia Woolf review was damned irritating – She belongs to a group of Bloomsbury people who are all over 40 and have taken on themselves the burden of being modern and all very promising and saviors of letters…They live for their Literary reputations and believe the best way to keep them is to try and slur off or impugn the honesty of anyone coming up…”

After Virginia criticized Edith Wharton in her “American Fiction” essay, Wharton also wrote a letter to a friend complaining about it:

“Mrs. Virginia Woolf writes a long article…to say that no interesting American fiction is, or should be, written in English; and that Henry Hergesheimer [sic] and I are negligible because we have nothing new to give–not even a language! Well–such discipline is salutary.”

As much as Virginia admired America, she made plans to visit the states twice in her lifetime but never actually went. In 1938, just a few years before her suicide, Virginia wrote an essay titled “America, Which I have Never Seen” in which she imagined what America and its inhabitants are like:

“‘The Americans themselves,’ replies Imagination, ‘are a most remarkable people. Superficially, they differ little from ourselves. That is to say, they wear petticoats and trousers; marry and bear children. But whether it is that the mountains are so high and may at any moment belch out fire and decimate a town, or that the rivers are so huge and may at any moment roll out their long liquid tongues and swallow up a city, or that the air is decidedly alcoholic so that everyone is always a little tipsy, the Americans are much freer, wilder, more generous, more adventurous, more spontaneous than we are. Look how they battle and punch, hack and hew; tunnel through mountains; erect skyscrapers; are ruined one moment, millionaires the next. In the same span of time we [British] should have earned a modest pension, acquired a villa in Surrey, and decided, after due deliberation, to lop the cherry tree on the lawn. But the best way of illustrating the difference between them and us is to bid you observe that while we have shadows that stalk behind us, they have a light that dances in front of them. That is what makes them the most interesting people in the world – they face the future, not the past.”

Sources:

The Saturday Review of Literature; American Fiction; Virginia Woolf; August 1 1925: http://www.unz.org/Pub/SaturdayRev-1925aug01-00001a03

The Dublin Review; Virginia Woolf’s America; Andrew McNellie: http://thedublinreview.com/virginia-woolf%E2%80%99s-america/

“Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences”; James R. Mellow; 1992