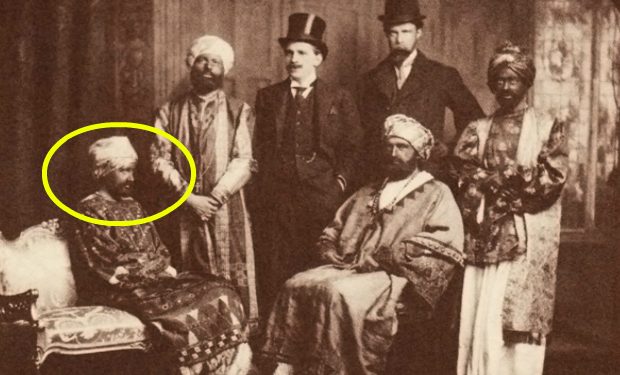

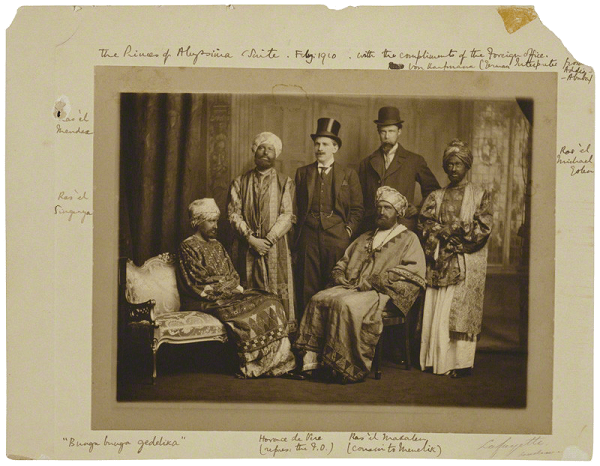

The Dreadnought Hoax was a practical joke that Virginia Woolf and her friends played on the British Navy when they disguised themselves as Abyssinian princes and convinced the navy to give them a private tour of Britain’s flagship, the H.M.S. Dreadnought.

The prank occurred in February of 1910, when the group of friends, which included their ringleader Horace de Vere Cole, Virginia’s brother Adrian Stephen, Guy Ridley, Anthony Buxton, Duncan Grant as well as Virginia Woolf (who was then Virginia Stephen), disguised their skin color with skin darkeners, dressed up in long caftans, placed turbans on their heads and glued fake beards to their faces.

After disguising themselves, the group then sent a telegram to the navy announcing their intended arrival at the ship and headed to London’s Paddington station.

At the station, Cole introduced himself to the stationmaster as Herbert Cholmondeley of the UK Foreign Office and asked for a special train to take them to Weymouth. Fooled by their disguises, the stationmaster supplied them with a private coach.

Once they arrived in Weymouth, they were greeted by an honor guard and taken to Dorset, where the ship was moored. There the group inspected the fleet and took a private tour of the Dreadnought.

Throughout the tour, the “princes” spoke in Swahili as well as random gibberish, proclaiming “Bunga! Bunga!” over and over, asked for prayer mats and awarded various crew members with fake military honors.

Adrian and Virginia also found themselves shaking hands with their cousin, who was an officer on the ship, but even he failed to recognize them through their disguises.

After a few hours, Adrian declared the state visit was over and asked to be taken back to Weymouth. During the ride home, the pranksters decided not to tell the press about their little joke in order to spare the navy any further embarrassment. The next day, Cole wrote a letter to a friend praising the naval officers:

“They were tremendously polite and nice – couldn’t have been nicer: one almost regretted the outrage on their hospitality.”

Always the attention-seeker, Cole went to the press anyway without telling the others. Within a few days the hoax was front page news.

Upon learning that a young woman had taken part in the prank, the press discovered Virginia’s identity, as well as the identity of the others, and appeared at their homes asking for interviews, which they granted. The public fascination with the hoax lasted well over a week before it eventually died down.

According to various newspaper reports, in retribution for their actions, several members of the group were later abducted by the navy and caned.

One article, published in the Evening Post in New Zealand in April of 1910, states that two unnamed hoaxers were caned, yet according to a recent article in the Guardian, only Duncan Grant was caned.

The prank spurred the British military to tighten restrictions on all future state visits by foreign ambassadors. After the real Emperor of Ethiopia visited England later that year, he was chased through the streets by children shouting “Bunga! Bunga!” and when he asked to inspect the navy’s fleet, the admiral politely declined out of fear of further embarrassment.

Sources:

Alberge, Dalya. “How a Bearded Virginia Woolf and Her Band of “Jolly Savages” Hoaxed the Navy.” The Guardian, 4 Feb. 2012, www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/feb/05/bloomsbury-dreadnought-hoax-recalled-letter

Bell, Quentin. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. Hartcourt Books, 1972.