The following is a guest post by Gloria Buckley. Buckley is a member of the Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain and has just completed her Master of Arts with Distinction in English Literature at Mercy College. She is a practicing lawyer for many years. Her poetry has appeared in several literary magazines and she published a collection of poetry entitled Just Visiting in 1991 that remains available on Amazon.com. She has had articles on Edgar Allan Poe, Merlin in Arthurian Legend published by a peer review Journal of English Language and Literature. Her love of Virginia Woolf’s works dates back to high school and her undergraduate English Literature studies at Seton Hall University. She is planning an additional M.A. and Ph.D. in Celtic studies from University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

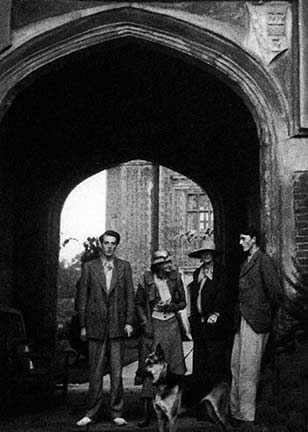

Virginia Woolf (hereinafter referred to as “Virginia” or “Woolf”) and Victoria (“Vita”) Sackville-West (poet, writer, aristocrat) met on December 14, 1922 and embarked upon a friendship and connection that remained until Woolf’s death in 1941.

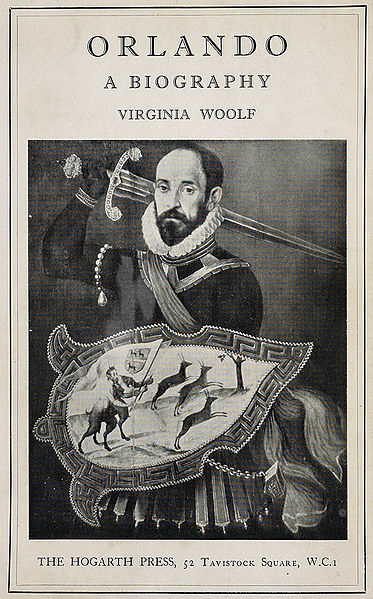

The relationship ignited creative genius in both women, in particular, in 1928, Woolf created the novel Orlando: A Biography (“Orlando”) a parodical historiography of Orlando the nobleman who becomes a woman spanning some three hundred years.

Woolf created Orlando as a tribute to Vita, to Vita’s family owned castle Knole so that as Vita’s son Nigel Nicolson writes that “the novel identified her (Vita) with Knole forever” (Nicolson 208). In this identification is Virginia’s “longest and most charming love letter in literature” (Nicolson 202).

In this literary exchange, Woolf and her husband Leonard published many successful works for Vita. While a short-lived romance occurred between Vita and Virginia, what truly remained immortal was a landscape of love that transcended all borders.

Orlando created a space, a “landscape” that honored Vita’s love for Knole which as her granddaughter Juliet Nicolson writes that “she was in no doubt that her relationship with Knole ‘transcended her love for any human being’” (J. Nicolson 102).

It is in this framework of geographical borders that the two women initially unite and then divide. Yet, the landscape love story remains transcending time, space and perhaps, even death as immortalized in Orlando.

Later in 1930 Vita and her husband Harold Nicolson (“Hadji” or “Harold”) would purchase Sissinghurst Castle which became Vita’s landscape for solitude, beautiful gardens, the peace/piece of Knole.

While Virginia’s competition for attention from Vita spanned family, husband, other romances, the true divide would be Vita’s love for Sissinghurst. Vita retreated to her pink towers of solitude and writing.

As Woolf’s “Orlando would act for Vita as a kind of moral compensation for the loss of Knole” (Orestano 48), Sissinghurst became her solitude. In Sissinghurst, Vita crossed all borders in time, ancestry and soil. Primogeniture laws could never take Sissinghurst away from Vita as Knole was bequeathed to her male cousins.

However, Sissinghurst would ultimately take Vita away from Virginia who seemed to be more or less a lady in waiting while Vita lived life. In fact, as Virginia’s nephew Quentin Bell writes that “on March 10, 1935 the Woolfs drove in a snowstorm to Sissinghurst to see Vita. As they took their leave Virginia realized that their passionate friendship was over” (Bell 183) (DeSalvo 213).

The emotional juxtaposition of land against Virginia’s eternal longing for Vita would ultimately turn from a literary joke in Virginia’s Orlando to Virginia’s desperation.

In May 1932, Virginia writes to Vita as follows: “there’s only one person I want to see, and she has no burning wish for anything but a rose red tower and a view of hop gardens and oasts” (DeSalvo Letters360). This tension would last until Woolf’s suicide in 1941.

The tension that underlies the relationship as Louise DeSalvo writes triggered Woolf’s own early loss of her mother, Julia Stephen who died early on in Woolf’s life.

Vita’s inaccessibility first in travels with Harold and then latter in her refuge at Sissinghurst may have “stirred up the feelings of separation that Woolf had experienced as a child and that are so poignantly explored through the responses of several characters in To the Lighthouse.

Once Woolf had written through the history of her separation from her mother, she may have needed to write a book in which she could possess Vita utterly: Orlando” (DeSalvo 204).

Woolf created in Orlando a borderless fantasy place where Vita owned her 365 room Knole above and beyond Kentish inheritance laws which prevented a woman from inheriting land (DeSalvo 205).

This great gift transcended time, rules and Woolf even allowed Vita to be a man who became a woman but still retained her identity or core. Woolf writes in Orlando that “Orlando had become a woman-there is no denying it.

But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been” (Woolf 64). Vita’s son Nigel Nicolson wrote that “Virginia by her genius had provided Vita with a unique consolation for having been born a girl, for her exclusion from her inheritance, for her father’s death earlier that year” (Nicolson 208) (De Gay 70).

Jane De Gay confirms that “Orlando demonstrates that imagination and empathy provide more powerful ways of staking a claim to the past than either patrilineal inheritance laws or conventional models of history” (De Gay 70). Woolf was able in Orlando to find for women a place; a room not just of their own but that they owned outright.

Ironically, Woolf also won temporarily Vita’s heart and in some manner crossed borders in possessing Vita for a while with the romance of such a gift.

Upon reading Orlando, Vita writes to Woolf that “you have invented a new form of Narcissism, -I confess, -I am in love with Orlando-this is a complication I had not foreseen. Virginia my dearest, I can only thank you for pouring out such riches. You made me cry with your passages about Knole, you wretch” (DeSalvo 289). Woolf was able to transcend all limitations, including, perhaps her feelings for Vita. A gift that conceived the return of home wrapped with love and comedic parody.

In Orlando, Woolf writes about Orlando/Vita as follows” “the English disease, a love of Nature, was inborn in her” (Woolf 66). Woolf takes it further and writes “her God was nature” (66).

Throughout the novel descriptions of Knole line the pages in poetic prose such as “she could see the undulating and grassy lawn; she could see oak trees dotted here and there; she could see the thrushes hopping among the branches… then appeared the roofs and belfries and towers and courtyards for her own home” (69).

Knole is described always as her home, her own home. While Orlando time travels over three hundred years and various countries, she returns home always to her castle and ultimately the novel lands in 1928 where she is at home.

Saeed Yazdani and Nastaran Shahbazi note that “Orlando’s home is mentioned frequently throughout the novel. It appears as a static and safe element in a chaotic and changing world.

The house symbolically has 365 bedrooms and fifty-two stairways (the number of days in a year, and the number of weeks in a year, respectively). It is significant that the house is marked by static, traditional measures of time, because the house provides regularity for Orlando, something she can always return to when she tires of her adventures in London or Turkey.

Thus, it reminds the reader that while the narrative itself may skip over decades or centuries, Orlando continues to live within a framework. Time, as a concept constructed by her ancestors, encompasses Orlando and provides her a home” (Yazdani 14).

Never does the reader doubt that Orlando can think and be internally a man, woman, or both and transcend gender as well as time and most importantly always return and control her home.

This beautiful paradox speaks to women even today that you must have a place of beauty, solitude, security that truly is yours no matter who you are. This flew in the face of Victorian limitations. Woolf rewrote history in the present moment and created a borderless paradigm for female security.

Unfortunately, for both Vita and Virginia, World War II created a terrifying landscape of war planes, bombings of the Woolf’s home in London and ultimately Virginia’s suicide in 1941 as she exited the terror with rocks in her pockets into the river Ouse and drowned. Both women retreated. Vita in Sissinghurst. Virginia into a world of terror, loss of family members, voices in her head, the fear of never writing and perhaps some form of mental illness that ultimately lead her to suicide.

Thus, the strength, the nobility, the independence of Orlando and the words of Woolf in A Room of One’s Own vanished into the waves. Woolf wrote in The Waves a prophetic foreshadowing of the landscape of suicide as she writes “Against you I will fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death! The waves broke the shore” (Woolf 170). Vita retreated in later years into the refuge of Sissinghurst, her garden and her writing.

In Sissinghurst, Vita’s roses transcend all time. The roses as Francesca Orestano opines are “inextricably tied to the land from which it grows, the rose provides us with a clue to the nature of the relationship here examined.

At Knole, in Orlando’s house, at Sissinghurst, roses are represented by a vast family or types of varieties, ranging from the most noble and selected aristocratic scions to the most common, wild and obscure among them.

Vita’s garden, an entire social history could be told by acknowledging the presence of roses” (Orestano 58). Sarah Raven writes that “this difference between old and new is brilliantly blurred” (Sackville-Raven 684).

In Sissinghurst as in Orlando, Vita crosses all borders in time, ancestry and soil. She creates with Harold an immortal rapture of her soul in the plantings and design. It bespeaks the very thorns that Vita’s hands may have touched and the soil she so selflessly tilled.

Vita writes in her poem “Sissinghurst” (Sackville 331):

This husbandry, this castle, and this I

Moving with the deeps,

Shall be content within our timeless spell,

Assembled fragments of an age gone by,

While still the sower sows, the reaper reaps,

Beneath the snowy mountains of the sky,

And meadows dimple to the village bell.

So, plods the stallion up my evening lane,

And fills me with a mindless repose,

Wherein I find in chain

The castle, and the pasture and the rose.

So, it is that Sissinghurst was a landscape for Vita “that caught instantly at her heart and imagination” (Orestano 49). Vita lived on in her imaginative strength and consumed within her “the disease for the love of nature” (Woolf 66).

If Virginia hadn’t committed suicide, would greater pieces have been written by each as they encouraged one another’s creativity? For as Nigel Nicolson wrote Virginia was fun and noticed them as children. Her kindness radiated. (Nicolson 200).

Perhaps, if Virginia had ventured to stay at Sissinghurst for an extended period of time something of the walls would have dropped for both writers.

This is all pure conjecture but one can’t help but wonder: what if they created a piece together, literally combining sentences, thoughts, styles and dreams all in one work? What if the borders were stretched and blended. Both descriptive intellectuals, both poetic prose, Vita careful and controlled and Virginia within the rapture of her poetic stream of consciousness. What visitation? What haunting would have ensued? Would Orlando emerge again but not as part man or part woman?

Orlando may have emerged as mystical, transcendental, prophetic, ageless, genderless and ethereal. The blended borders may have created the ultimate protagonist. The ultimate landscape of history and modernity may have been created by blending the two artists.

In a landscape of blended borders perhaps what would have been written would feel as follows (Buckley 1 13 17):

MY BELOVED

I remain eternally

The salt of my own earth

The pathways put beneath

Your feet

I picked and labored

With Hadji

All in symmetrical unison

Vantage points

Always leading to my heart

My magical Sissinghurst

Muted mauve tower.

You may gaze but don’t touch

The very places where

The imprint of my hands

Remain

And if in your heart

You wish to walk with me

Arm and arm

I will guide you

Now in my eternal peace.

For a vision of my morning misty, dusty hills

That harbor the echoes of my green Yew Hedge

Hugs

I so deeply love

Are more majestic than life itself

And if you don’t agree

Than you are more

Dead than I.

Virginia my mystical voyeur

To all my wild imaginings

Stands truant in poetic observation

Memorializing, still, my every move

A genius to capture my essence

My earth

That pours like muddy chocolate down my hands.

My virile images she retained

And cast with Orlando freely

Like her murderous

Stones upon the sea

She lulls herself to sleep

Weary of my magnetic

Frenzy

To create immortal rose blooms

That never vacate my boot print paths.

Applaud me with triumphant praise

My powerful preservation

A legacy of love

My Sissinghurst

My beloved

My soul.

As Orlando dips his quill into the ink to write yet another poem, Woolf tells us her ideas about writing, impressions and memory. Woolf tells us that ”Memory is the seamstress, and a capricious one at that. We know not what comes next, or what follows after. Memory is inexplicable” (Woolf 36).

The immemorable landscape of artistic trust and love between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville perhaps has only begun.

Works Cited

Bell, Quentin. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. Harcourt Inc. New York: (1972). Print.

De Gay, Jane. “Virginia Woolf’s Feminist Historiography in “Orlando””. Critical Survey.19.1.62-72.Web. Jstor. 9 Jan. 2017.

DeSalvo, Louise A. “Lighting the Cave: The Relationship between Vita Sackville-West and VirginiaWoolf”. Signs. 8.2 (1982). 195-214. Web. Jstor.27 Dec. 2016.

DeSalvo, Louise and Mitchell Leaska. The Letters of Vita Sackville-West Virginia Woolf (“Letter”).California: Cleis Press. (1984). Print.

Knopp, Sherron E. “‘If I Saw You Would You Kiss Me?’: Sapphism and the Subversiveness of VirginiaWoolf’s Orlando”. PMLA.103.1. (1988). 24-34. Web. Jstor.5 Dec. 2016.

Nicolson, Juliet. A House Full of Daughters: A Memoir of Seven Generations. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. (2016). Print.

Nicolson, Nigel. Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West & Harold Nicolson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1973). Print.

Orestano, Francesca. “Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Knole and the Creation of Sissinghurst: ‘A Green Thought in a Green Shade’”. Cultural Perspectives.13. (2008). 38-62. Web. Jstor.13 Jan. 2017.

Sackville-West, Vita. Selected Writings’. Mary Ann Caws. New York: MacmillanUSA.1973.Print.

Sackville-West, Vita & Sarah Raven. Sissinghurst. New York: St. Martin’s Press. (2014). Print.

Woolf, Virginia. Orlando. The University of Adelaide Library. South Australia: (2015). eBooks Adelaide.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. New York: A Harvest Book Harcourt, Inc. 1931. Print.