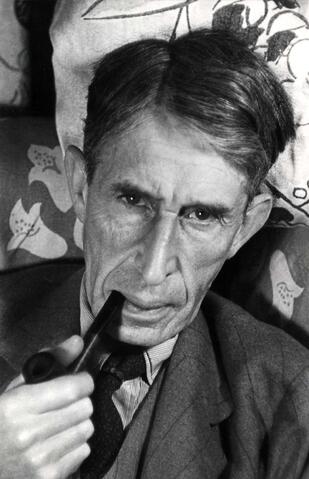

Virginia Woolf’s death in March of 1941 brought an end to her 29-year-long marriage to Leonard Woolf.

After her death was announced in the press, Leonard, who had nursed Virginia through many years of mental breakdowns and suicide attempts, received a flood of condolence letters from friends and fans, yet he was inconsolable.

According to the book Leonard Woolf: A Biography, in a state of grief, Leonard scribbled the following on a loose piece of paper:

“They said ‘Come to tea and let us comfort you.’ But it’s no good. One must be crucified on one’s own private cross. It is a strange fact that a terrible pain in the heart can be interrupted by a little pain in the fourth toe of the right foot. I know that V. will not come across the garden from the Lodge, and yet I look in that direction for her. I know that she is drowned and yet I listen for her to come in at the door. I know that this is the last page and yet I turn it over. There is no limit to one’s stupidity and selfishness.”

Leonard had Virginia’s body cremated, during which the crematorium played a recording of “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” by Gluck. Afterward, Leonard came home and went for a long walk with his friend Willie, who later wrote an account of their conversation that day:

“He [Leonard] spoke with terrible bitterness of the fools who played the music by Gluck…which promised some happy reunion or survival in a future life. ‘She is dead and utterly destroyed,’ he said, and all his profound disbelief in religion and its consolations were present in those words. It was impossible to comfort him in his loneliness and sense of loss…I referred to her belief which he had mentioned in his letter that she thought she was going mad and would not recover this time, and I said we must believe that her belief was right. He denied this passionately and said ‘No, she could have recovered as she had done from previous attacks.’”

In Leonard’s autobiography The Journey Not the Arrival Matters, Leonard wrote about how he and Virginia had always wanted the cavatina from Beethoven’s B flat quartet, Op. 130, to be played during their cremation because there is a gentle lull in the middle of the song that seems like an opportune moment for “gently propelling the dead in the eternity of oblivion.” Yet, when it came time to make the arrangements for Virginia’s cremation, Leonard was so overwhelmed with grief he couldn’t bring himself to request the song and instead played it that evening when he was home alone.

Leonard buried Virginia’s ashes under one of the two intertwined Elm trees in their backyard, which they had nicknamed “Virginia and Leonard,” and marked the spot with a stone tablet engraved with the last lines from her novel The Waves: “Against you I fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death! The waves crashed on the shore.”

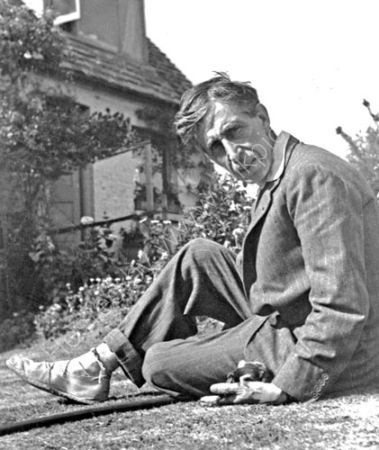

In the months that followed Virginia’s death, Leonard continued to lead his quiet life at his home in Rodmell, named Monk’s House. His friends advised him not to stay in the house alone but he refused to leave, stating: “It is no good trying to delude oneself that one can escape the consequences of a great catastrophe.” Leonard answered condolence letters, continued to run the Hogarth Press and commissioned a fellow writer to write a book about Virginia, which never came to fruition. Yet, eventually he longed for London, according to his autobiography:

“After Virginia’s death I felt that I must have someplace where I could stay in London in order to be able to do my work there more intensively. So I took a flat in Clifford’s Inn.”

After realizing he disliked the small size of the flat and the close proximity of his neighbors, he decided to move back to his old home in Mecklenburgh Square, which had been damaged by German bombs:

“I could not stand Clifford’s Inn for long, and in April 1942 I got three rooms in my house in Mecklenburgh Square patched up and moved in there. ‘Patched up’ is the right description of the rooms and the house. There were no windows and no ceilings, and nothing in the house, from roof to water pipes, was quite sound. I got my loneliness and my silence (except when the bombs were falling) all right. But I have experienced few things more depressing in my life than to live in a badly bombed flat, with the windows boarded up, during the great war. I stuck it out in Mecklenburgh Square for exactly a year, but by October 1943 I could bear it no longer and took a lease at 24 Victoria Square.”

During this transition phase following Virginia’s death, a curious thing happened. Leonard fell in love. Her name was Trekkie Parsons and she was the sister of one of Leonard’s close friends, Alice Ritchie, who was dying of cancer and had requested a visit from Leonard.

During Alice’s long battle with the disease and Leonard’s frequent visits, Leonard became close with Trekkie, who was an artist, and before he knew it, he fell madly in love with her, despite the fact that she was married and more than 20 years his junior.

The two began a curious love affair that would last the rest of Leonard’s life. During their long relationship, Trekkie split her time between Leonard and her husband, who knew all about her affair with Leonard and accepted it. When Leonard was living in Mecklenburgh Square, Trekkie stopped by on Monday nights after her lithography class for a boiled egg, tea and toast.

After Leonard moved back to Rodmell, she stayed with him in the home throughout the week and then returned to her husband on the weekend. When Leonard and Trekkie were apart, the two sent each other poetry and love letters and Leonard would whine about not being able to see her enough.

Trekkie was not just a romantic companion for Leonard but also an intellectual one. In a letter he had written to her, he explained that she embodied his belief in “the value of art and and of people and of one’s relations with people. You combine all three values for me and as I said the you which I know to be you is the most beautiful person I’ve known…I love you.”

Although they were a couple, much like his relationship with Virginia, Leonard and Trekkie’s relationship was not sexual. Like Virginia, Trekkie was also wary of sex but also felt it was important to remain loyal to her husband, at least intimately.

Trekkie was very much like a wife to Leonard, cooking most of his meals, redecorating his home in Rodmell, listening to music with him in the sitting-room after dinner (like he had done with Virginia) and going away on holidays and vacations with him.

Leonard continued his writing career after Virginia’s death, publishing the third volume of his series After the Deluge in 1953, his five-volume autobiography and A Calender of Consolation in 1967. He also served as the editor of the Political Quarterly, served on the Board of Directors for the New Statesman and continued to run his publishing press, Hogarth Press.

Leonard also continued to work in politics, working for the Labour party as the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on International Relations and the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on Imperial Questions and also served as a chairman on the executive committee for the Fabian Society.

In 1960, Leonard revisited Sri Lanka, where he had served as a civil servant in his youth and was surprised by the warm reception he received.

Around 1962, American playwright Edward Albee wrote to Leonard and asked for permission to use Virginia’s name in a play he had written, titled Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Leonard not only gave his permission, but he also went to see the play when it came to London. He later wrote to Albee, praising the play as “so amusing and at the same time moving and is really about the important things in life,” and mentioned a similarity between it and a short story Virginia once wrote titled Lappin and Lapinova.

In 1964, Leonard accepted a honorary doctorate from University of Sussex and in 1965 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Leonard also gave numerous print, television and radio interviews during his lifetime, discussing everything from his life with Virginia, to the Bloomsbury Group as well as his own personal thoughts on suicide and mental illness.

When Leonard passed away on August 14 in 1969, he left Trekkie his entire estate, including his manuscripts and publishing rights. She later transferred these publishing rights, his papers and Monk’s House, to the University of Sussex. Leonard’s body was cremated and his ashes were buried, alongside Virginia, in their backyard in Rodmell.

Sources:

“The Journey Not the Arrival Matters”; Leonard Woolf; 1970

The New York Times; Trekkie Parsons; 93, Artist in Bloomsbury Group; August 1995

“Leonard Woolf: A Biography”; Victoria Glendinning

The Guardian; A Fresh Spirit; Victoria Glendinning; August 2006

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2006/aug/26/featuresreviews.guardianreview27

University of Sussex: Leonard Woolf Archive

http://www.sussex.ac.uk/library/speccoll/collection_descriptions/leonardwoolf.html