The following is a guest post by Kirsty Hewitt. Hewitt is in her final year of a Research Master’s degree at the University of Glasgow, following a taught Master’s at King’s College London. She is currently writing a dissertation which examines the female body and mind through work by Simone de Beauvoir, Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Jeanette Winterson, and Ali Smith. She has been fond of all of these authors since discovering them during the voracious reading of her teenage years:

In ‘Woolf and the Private Sphere,’ Laura Berman discusses the disparity between public and private spaces as Woolf herself interpreted them, and the relation which gender had upon this. Using two of Woolf’s essays as a standpoint, Berman writes:

“Woolf’s celebrated essay A Room of One’s Own makes clear the feminist implications of a woman’s access to private space, while her late feminist essay Three Guineas describes women as poised on ‘the bridge which connected the private house with the world of public life’, torn between the opportunities and burdens of each.”

The private house as a haven of one’s own is of importance to Woolf, although the same can be said about a woman’s need for a private space to call her own, in which she can work on what she wishes, away from male interference.

The ability of women to catalogue books, and to work on mathematical concepts in private spaces within two works by May Sinclair and Woolf herself, will be demonstrated in this essay.

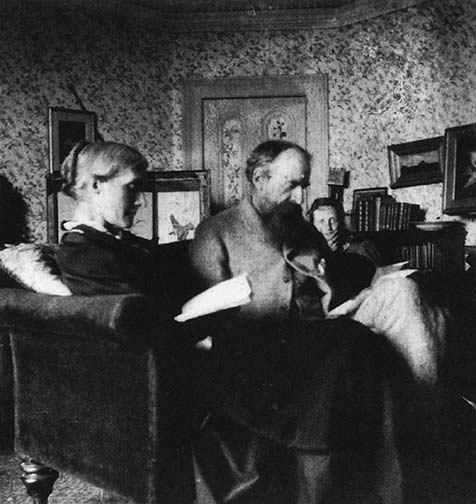

Raised as she was in a patriarchally dominated world, Woolf’s upbringing was still more liberal than most; she was allowed to visit and borrow tomes from her father’s large library.

Still, the mores of society prevented her from attending school as her brothers were expected to and, as Berman writes, “Leslie Stephen’s study always remained his masculine preserve.”

Berman uses the word ‘sanctuaries’ to describe the partition between the male and female world within the shared home in her essay; this reinforces the Victorian societal stereotype in which the Angel of the House mentality prevailed, in which every woman was expected to perform a myriad of duties, from cleaning to looking after any offspring – unless she was privileged enough to afford outside or live-in help. The male was simply allowed an isolated space in which to rest, away from the “real world,” as it were.

Berman believes that “… Woolf conceives of the public sphere neither as an escape from the failures of public life nor as a prison for domesticated women, but as a potentially generative, though problematic, site for the reordering of personal, social, and political relations.”

This proposed shift toward allowing women the agency to inhabit previously male-dominated spheres – for instance, the library and the study – is demonstrated in the decision which Woolf herself shared with her brother Thoby to move to a minimalist dwelling following the death of their father, in which no rooms were barred to her.

Such a choice was a progressive one, and it can certainly be said that it allowed Woolf an architectural freedom of sorts when compared to conventional habitats expected to be populated by women within society.

Another marked distinction which ran alongside separate male and female spheres within the home – in which different rooms existed for distinctly gendered purposes – was that traditionally, children were separated from parents.

They were largely banished to the upper floors where the nurseries were situated, and looked after largely by nursemaids, a reversal of responsibility from maternal – or paternal – nurturing.

Evidently, this was only an option for the well-to-do, but it is one which existed within Woolf’s life. Thus, a separate sphere entirely was created, and there was a real distancing created between parents and their offspring.

Berman’s central idea in ‘Woolf and the Private Sphere’ can be taken and applied to two of my chosen thesis texts. In May Sinclair’s The Divine Fire (1904) and Virginia Woolf’s Night and Day (1919), full entry to the male sphere is withheld to both female protagonists upon grounds of gender; regardless, it can be said that both Lucia and Katharine eschew tradition in that at times, they are able to partially inhabit the male sphere.

In Lucia’s case, one could argue that she is allowed the freedom of the library due to the assistance which she affords to Savage Keith Rickman, but Katharine’s case is markedly different.

In The Divine Fire, Lucia Harden works alongside male protagonist Rickman in a secluded Devonshire library belonging to her family, which is revered as one of the best private collections in the country.

The job which Rickman is hired for, and which Lucia begins to assist with, is that of cataloguing the library after her father Sir Frederick’s death. Rickman, of course, has far more agency within this space, due not only to his gender; such a task is his trained profession, and he receives payment for his work.

Lucia receives no monetary settlement for her efforts, but enjoys being in a less feminine domain nonetheless in her role as “collaborator.” She is ejected from joining such a profession as Rickman’s solely due to her gender; her ability, willingness, and drive to learn are never taken into account.

In a way, Lucia echoes Woolf’s position; she too, with her bright mind and the legitimacy that access to centuries of learning brings, was allowed access to the library during her formative years.

Regardless, despite the library not being in Rickman’s possession, his very presence demonstrates male privilege:

“For he [Rickman] and she [Lucia] could only meet in an ideal and fantastic region, and he served her in an ideal and fantastic capacity, on the wholly ideal and fantastic assumption that the library was hers.”

Tradition and familial expectations dictate that rather than leave Lucia the library and its books, everything should be sold, and the entire collection is thus mortgaged to a London-based financier. Whilst her father allowed her to use the space – which she did freely – he is still not of the mind that a woman should be able to inherit such things.

Due to her gender, she is unable to assume the privilege that would allow ownership to pass to her as an adult, and traditional patriarchal dominance thus remains firmly in place. Indeed, Sinclair writes:

“The chronicler who recorded that no woman had ever inherited the Harden Library contented himself with the bare statement of the fact. It was not his business to search into its causes, which belonged to the obscurer reasons of psychology.”

As in many households of the period, ‘It was a tradition in the family that its men should be scholars and its women beauties, occasionally frail’ There are so few expectations for her that Lucia could easily drift through life, achieving nothing, and, in doing so, she would merely be following in the footsteps of her female ancestors.

She is unfailingly aware of this, but still holds a willingness to assist with the task; the contents of the room are still precious to her, regardless of ownership rights.

She does, however, pass across gendered boundaries when she shuns domesticity; it is not her duty to dust the books, despite Rickman’s caution that they could become damaged if not cleaned properly.

Her silent refusal to perform this task thus places her bodily in a kind of hinterland between male and female spheres; she does not embrace feminine domesticity, but neither is she allowed to inhabit a masculine sphere without consequences.

The very way in which she places herself within the unfeminine space of the library gives her agency; she is working at something outside her own sphere which is unexpected of her, and which she proves to be rather good at.

Sinclair’s description of Lucia bridges the gap between the purely masculine and excessively feminine, having, as she does, traits of each which are dominant within her:

“By a still more perverse hereditary freak the Harden intellect which had lapsed in Sir Frederick appeared again in his daughter, not in its well-known austere and colourless form, but with a certain brilliance and passion, a touch of purely feminine uncertainty and charm.”

One can relate this without too much trouble back to Woolf’s own experience; she grew up with two brothers, and the influence of her father and the Bloomsbury Group respectively, and whilst she was supposed to show the very essence of femininity at all times, she was able to discuss masculine matters – such as the infamous “semen” conversation with Lytton Strachey – and play her part in unladylike pranks such as the Dreadnought Hoax, in which she disguised herself as a male member of the Abyssinian royal family.

This emphasises, again, the vast difference which could, and did, exist between gender expectations and gender performance. Both Lucia and Katharine can be said to use their intellect in ways which veer away from the feminine, and put them on the same level – at least in terms of ability – as male counterparts who are performing the same or similar tasks.

Night and Day moves away from the library and into the privacy of academia. Katharine Hilbery’s strength lies in the male-dominated sphere of mathematics, a pursuit which can have no real benefit to her as a woman in the eyes of Victorian society.

She has undoubted skill, but is ultimately pursuing something within the male sphere. Katharine personally recognises that her fondness for mathematics goes against the gender expectations which both her family and society hold for her:

“There was something a little unseemly in thus opposing the tradition of her family; something that made her feel wrong-headed, and thus more than ever disposed to shut her desires away from view and cherish them with extraordinary fondness.”

Some of the reasoning which Woolf gives the reader as to Katharine’s area of interest is that she is loath to follow her mother’s example and write stuffy biographies of past forebears; rather than embed herself purely within the past, she works toward a future where such professions as mathematics are inclusive of her gender; a world where she can be recognised and perhaps even revered for what she is able to do.

In the present moment of Night and Day, however, Katharine feels secure only when she can study “furtive[ly] and secretive[ly]” by night, a time at which she is unlikely to be disturbed in her actions.

The sphere which Katharine is inadvertently disrupting is that of work, despite the location in which she does so being her home. This draws a striking similarity to The Divine Fire; both she and Lucia are practising a male pursuit in what should historically be a limiting space for them.

Woolf empathises with her protagonist when she writes: “Perhaps the unwomanly nature of the science made her instinctively wish to conceal her love of it.”

Relating to Berman’s original idea, Katharine balances the great divide between the public and private spheres. She does this by masking her inner desires to study; to all intents and purposes, she presents herself as an upstanding and proper young woman, whose wants never veer far from the norm:

‘It was understood that she was helping her mother to produce a great book. She was known to manage the household. She was certainly beautiful. That accounted for her satisfactorily’

Positioning Katharine in this way gives her a far-reaching interiority, allowing her agency to study – provided she does so in silence and in secret.

Both Lucia and Katharine – and, indeed, Woolf herself – can be said to have been given the legitimacy to enter male spheres due to their own obstinacy and intellects.

Whilst Lucia in The Divine Fire and Virginia in life were able to visit their home libraries, the death of Lucia’s father and of Leslie Stephen respectively lifts all restrictions on what they can and cannot respectably read, and the times at which they are allowed entry to these male rooms.

Katharine’s father takes little interest in her pursuit of mathematics, and her lack of a stable male partner allows her the time to spend on the workings which she so enjoys.

Woolf makes it clear to the reader that should she marry, Katharine’s studies, whether private or otherwise, would be rendered off-limits; through the institution of marriage, the world would lose yet another keen and capable brain.

Bibliography:

Berman, Laura, ‘Woolf and the Private Sphere’ (Virginia Woolf in Context, ed. Bryony Randall and Jane Goldman), pp. 461-471

Sinclair, May, The Divine Fire. Henry Holt and Company, 1904.

Woolf, Virginia, Night and Day. Duckworth and Company, 1919; repr. in Night and Day & Jacob’s Room, (Ware: Wordsworth Classics, 2012)